You know the rest. But no, this isn’t a nutrition posting; it’s actually some information about shoulder health and safety. As these exercises can also be done for hypertrophy to improve a bodybuilders physique, the topic has been double categorized under “Fitness Tips” and “Corrective Exercises”. What I’m writing about today are exercises for your Rotator Cuff musculature.

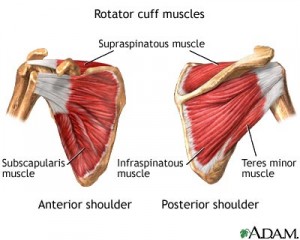

What is the Rotator Cuff? It is a group of 4 muscles in and around your shoulder joint. The area referred to as the shoulder is complex and involves multiple joint interfaces, but for our purposes we will be referring to the glenohumeral joint (the ball-and-socket), as that is what the muscles primarily affect when they act. Those muscles are:

Supraspinatus: acts to abduct your arm (raise it up to the side)

Infraspinatus: acts to externally rotate your upper arm (turning out your pockets)

Teres Minor: also externally rotates your upper arm

Subscapularis: acts to internally rotate your upper arm (wrapping your arms around yourself)

View of the RC

Collectively known as the SITS muscles, they act together to stabilize the “ball” (humeral head) of your upper arm (humerus) in the “socket” (glenoid fossa) of your shoulder blade (scapula). When these muscles are injured or weak, the ball can shift around in the socket, causing further weakness and instability in the control of your arm. Often, a chronically unstable shoulder leads to injuries such as subluxations, tendinitis, or neuropathies.

Who wants that?! No one! So what should you do to ensure a stable shoulder joint and prevent putting your orthopedist’s children through college? Here are a few exercises to add to your workouts that should be done every other day or so (every day if you have a history of ball-and-socket problems). They should be done for volume (high reps) with a lower intensity (weight) because these are postural muscles, programmed for the high endurance job of maintaining the same position all day. They should also be done at the end of the workout to avoid them being too fatigued to assist you in correctly executing your upper body exercises that day.

1) Empty Can (for supraspinatus): stand upright with good posture, arms down at your sides. As you raise your arms up and out on a 45 degree angle (not straight to the side, not straight out in front), keep your thumbs pointed towards the ground (as if you were emptying a can of its contents). Do not raise your arms higher than shoulder height and, in fact, it’s not necessary to go more than 30 degrees up because that is when your deltoid muscle takes over the movement from the supraspinatus. Traditionally the exercise is done to shoulder height, though. Perform 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions. Add weight conservatively as the exercise becomes easier.

Empty Can

Empty Can Finish

Empty Can Sideview

2) Side-Lying External Rotation (for infraspinatus/teres minor): lie on one side on the ground or a bench, say your left side. Have a rolled up towel held under your right arm, against your side, to keep your arm from being flush against your side. This puts the shoulder in a better anatomical position for the exercise. Begin with your right elbow bent to 90 degrees and your forearm across your abdomen. Keeping your upper arm in line with your torso the whole time, roll your right forearm out away from your torso, towards the ceiling and then slowly back down again. Do not rotate too far – if your right hand is going behind you, you are way too far. Perform 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions. Add weight conservatively as the exercise becomes easier.

Side-Lying Dumbbell External Rotation

Side-Lying Dumbbell External Rotation Upper

3) Standing 90-90 External Rotation (for infraspinatus/teres minor): this is one of the many variations on external rotation exercises. Stand upright with good posture (shoulder blades back) with your back against a wall. Raise your arms up to 90 degrees (but not more) against the wall. Bend your elbows to 90 degrees and place your forearms and the back of your hands flat against the wall. Slowly let gravity rotate your arms downwards so your palms are facing the floor (elbows still bent) and then actively roll them back up to the wall again. Perform 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions. Add weight conservatively as the exercise becomes easier.

Standing Dumbbell External Rotation

Standing DB External Rotation

It’s rare that anyone needs to exercise their subscapularis, as most people’s internal rotators are overly developed and tight. But for the sake of being thorough, here is one exercise. Do not overdo it. It is far more common to need work on the external rotators mentioned above. Always do more external rotator work than internal unless you have a diagnosed injury.

4) Standing Cable Internal Rotation (for subscapularis): stand with a cable machine to your right side, cable in your right hand, rolled up towel (again) under your right armpit. Maintaining the same good posture and arm positioning as for the Side-Lying rotation exercise, pull the cable and rotate your forearm in towards your body it touches your abdomen. Then slowly release the cable back out again. Your elbow should always be bent to 90 degrees, as if your forearm were sliding along an invisible table top in front of you. Do not let the cable yank your arm out, and do not rotate out to the side past your torso. Perform 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions. Add weight conservatively as the exercise becomes easier. **This can also be done as another external rotation variation if you turn and face the other way.

Standing Cable Rotation

Standing Cable Rotation2

Now you have a starter packet for shoulder health and safety. Not only will these exercises help keep you out of the doctor’s office, but they will make you stronger. When your weightlifting hits a plateau, make sure you are keeping up your rotator cuff strength, as that step has been shown to reinvigorate the upper body’s ability to handle heavier weight! Stable little muscles make bigger muscles fire more effectively and keep optimal alignment for torque, which means you can push more people around. Happy lifting!